Shimmering Waters of the Galápagos

- Nicole Pittoors

- Sep 28, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 30, 2024

(cross-posting from my Instagram)

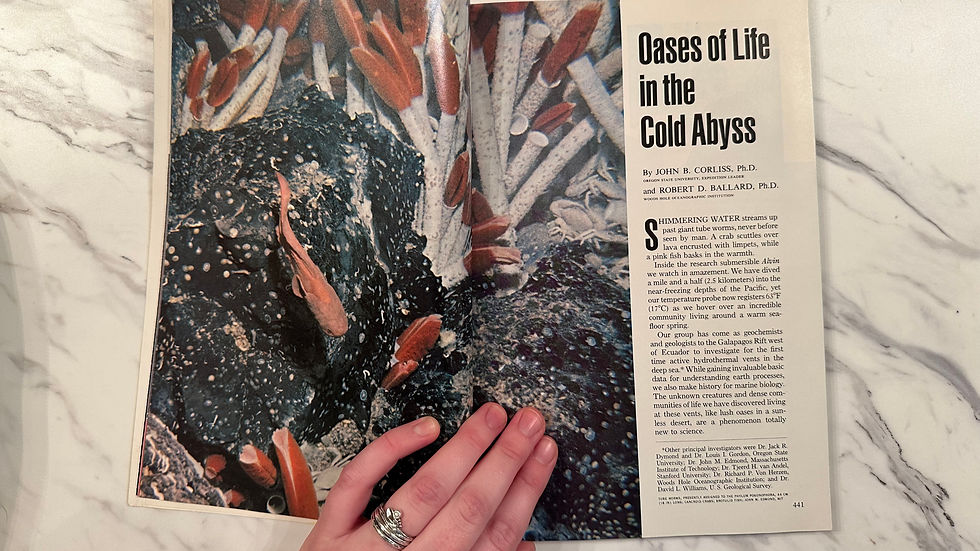

“Shimmering water streams up past giant tube worms, never before seen by man. A crab scuttles over lava encrusted with limpets, while a pink fish basks in the warmth. Inside the research submersible Alvin we watch in amazement. We have dived a mile and a half (2.5 kilometers) into the near-freezing depths of the Pacific, yet our temperature probe now registers 63°F (17°C) as we hover over an incredible community living around a warm sea-floor spring. Our group has come as geochemists and geologists to the Galápagos Rift west of Ecuador to investigate for the first time active hydrothermal vents in the deep sea. While gaining invaluable basic data for understanding earth processes, we also make history for marine biology. The unknown creatures and dense communities of life we have discovered living at these vents, like lush oases in a sunless desert, are a phenomenon totally new to science…

…How many more vents exist along the 40,000-mile-long system of oceanic rifts, we wonder? How many of these support life? And will their existence revolutionize our knowledge of life in the abyss?” -October 1977 Issue of National Geographic written by John Corliss and Robert Ballard

While reviewing my collection of National Geographic magazines from my great-grandfather, I came across one of my now most prized possessions—the issue describing the discovery of hydrothermal vents. I am still in awe that I was lucky enough to journey to these vents and spend a month at sea with the most incredible @schmidtocean crew and science team, where we discovered a new vent site here ourselves (Sendero del Cangrejo🦀). This expedition will always be in my heart and my (happily) sleep-deprived memory.

Details regarding the cruise mission and accomplishments: https://schmidtocean.org/cruise/hydrothermal-vents-of-the-galapagos/

Left: A deep-sea skate, Bathyraja spinosissima, observed in the Galápagos in 1977.

Right: Bathyraja spinosissima that we observed in 2023.

This species is thought to use the warmth from the vents to incubate its eggs.

One of the magnificent vent fields.

Alvinellid and Hesionid worms living within the flow of a chimney.

A Cirrotheuthid octopus.

More chimneys

Bamboo corals, a type of octocoral, can be found on the peripheral sea floor of hydrothermal vents and are often biolumenescent.

A chimera glides past the ROV.

Showing Jess all the different worms we had collected on a previous dive.

Having fun imaging Paralvinella grasslei, a terrebellid worm commonly found in the flow of hydrothermal venting on chimneys.

One of my favorite vent worms, Nereis sandersi.

Holding a giant clam, Calyptogena sp.

After detecting signals of hydrothermal venting via a suite of chemical sensors mounted on a CTD, we struggled to find the source until we came across more and more Munidopsid squat lobsters, which are commonly found on the periphery zone of vents. We then followed the path of sqaut lobsters until we found venting and giant Riftia pachytila tube worms!

A Riftia mound and Bathygraied crab at the newly discovered vent site Sendero del Crangejo (path of the crab). You can watch more about this discovery here:

Photos were taken by Alex Ingle (@alexinglephoto) and ROV SuBastian pilots from Schmidt Ocean Institute (@schmidtocean) and have been approved for use by the Galápagos National Park Service as part of Scientific Research Permit No PC-51-23.

Personal photos from exploring Santa Cruz:

Коментари